Thanks to lenient regulations on deposit taking in West Africa, what we now understand as microfinance is individual loans to microentrepreneurs with an established business in the retail sector, used for working capital and small investments in their business, paid back monthly from a current account often held in the institution (or a cooperating bank), from which they can pay bills, transfer money across the country (and beyond), save long-term deposits for a rainy day or a daughter’s university tuition abroad.1

But many laypeople have the image of Mohamed Yunus’ 2006 Nobel Peace Prize, following the International Year of Microcredit of 2005, presenting quite a different model. No long history into the susu, tontines, or self-help group systems here, but as a quick reminder, the model that catapulted the sector to the top of the world agenda could be represented by the following picture2:

A very poor woman selling handicrafts to earn a little more while she cares for her children, member of a group of women in similar trades, and borrowing very small amounts of money to increase production, productivity, or quality of product. Those loans were reimbursed daily/weekly, at very high interest rates by today’s standards (let’s remember that the Fed’s interest rate was around 22.36% in 1981). The loan was collateralised by the group – if a woman defaulted, it was up to the others to pay up – making credit risk quite manageable.

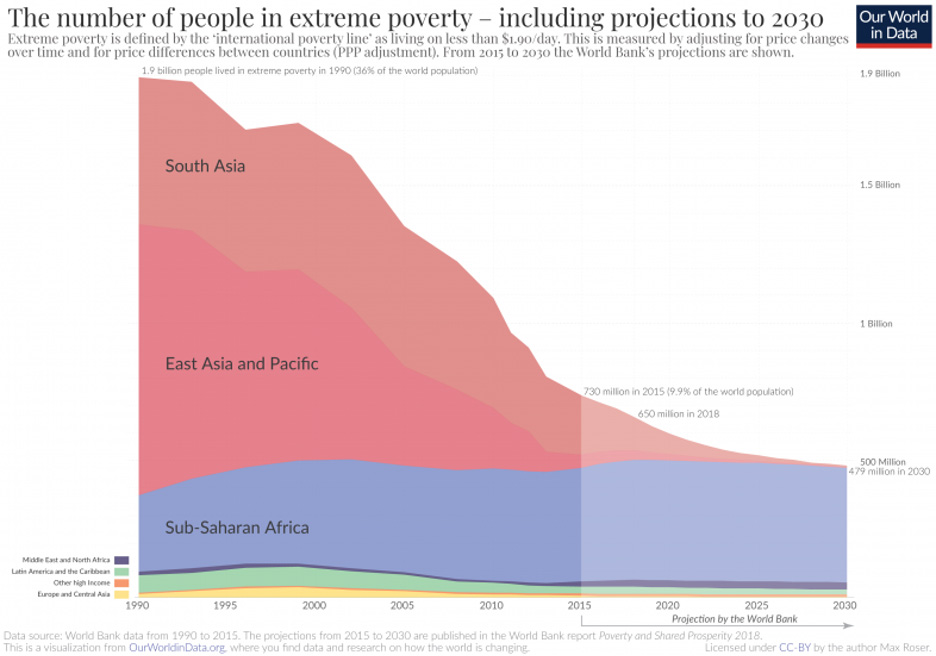

This model had phenomenal success. People and organisations invested. Microlending institutions grew. More and more women accessed loans to improve their livelihoods, and often became primary breadwinners. With the accomplishments, donors and NGOs started setting up microlending institutions throughout the globe, some of which have grown to multi-billion-dollar corporations traded on the stock-market. Where did they go, and where is that model going? The model was great for the very poor in peri-rural settings where traditional societal structures were still in place, where access to raw materials for the locally sourced, produced, sold and consumed goods were easily available, where very high marginal profits could be applied to very cheap goods. The model was expensive to run, requiring either a lot of investment in training the group in financial literacy and management, or high-touch loan officers, and often both. The products were simple and standardised. The high value-added on the cheap goods paid for the high interest rates, as long as there were no other cheaper products on the market. While the model allowed institutions running to grow exponentially, after all the share of nearly indigent women in the developing world in 1990 was high (see graph below), it did not allow for individual women to grow out of what they were doing: too small loans to truly invest in increased production.

Thus came individual lending. And savings products. And modernity brought cell phones whose use needed to be paid to keep using them. And that brought about digital financial services. The world continued to globalise, and individuals with a high-risk appetite started importing cheap goods to sell on local markets, which needed larger loans. Today, microfinance institutions really do function as banks in many respects.

So, will group-lending go the way of the dodo?

Maybe, but perhaps it is time for international donors, NGOs and governments to look at this model again with a more narrowed perspective, looking at areas of the world where financial inclusion is still too low, where poverty is still endemic, and how to launch new institutions that will support small societal networks to develop and reach into the modern world. Sub-Saharan Africa, as we can see from the graph3, is still such a place. Thankfully, billions of women have lifted themselves out of poverty in the past decades, but there are still too many women, and men, whose revenue flows are insufficient to build any kind of equity, and lay the groundwork for their children to build on. Too many children who cannot go to school because their parents cannot afford the tuition, books, and accommodation if there is no school in the vicinity, and those children are otherwise more useful to the family and to their society working in the fields or in the shop. That slows down the demographic revolution that societies need to continue building equity: if you need children to provide income, and cannot afford means of managing the size of your family anyway, the little wealth you accumulate continues to be split 10 ways at your death, instead of 7. Then 5. Then 3.

A tool is only useful if it is put to good use. Providing a mechanic that employs 2 people and his sons with a microloan that he pays each day or week does not make sense. Providing a woman selling vegetables with a microloan does. As long as there are the indigent barely getting by with what they can get their hands on, the Grameen model could continue to provide value. It will not end poverty, or malnourishment, or even provide the lift societies need to lift off into development – promises made in the early years that did not materialise. But if the tool is useful, why not put it to good use?

Footnotes

1 Picture Caption – A microfinance client and his employees operating a pineapple farm in Central Guinea.

2 Picture credit: https://www.yearofmicrocredit.org/

3 Graph source: https://ourworldindata.org/extreme-poverty