The role of finance in development

Appropriate financing for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) at national scales provides the “blood stream” that irrigates large corporations with raw materials and clients. In turn, demand and supply from corporations creates the growth necessary for SMEs to achieve economies of scale, grow, and generate employment1. In so called developed economies, SMEs represent between 60% and 70% of employment, while in developing economies employment in SMEs represent half of that2.

For all this potential, successful development of SMEs has been rough going, for a host of reasons. Some development professionals point to the lack of manager-ready human resources, many macro-economists point to developing economies being hooked on commodities where price swings on world markets can have profound socio-economic effects.

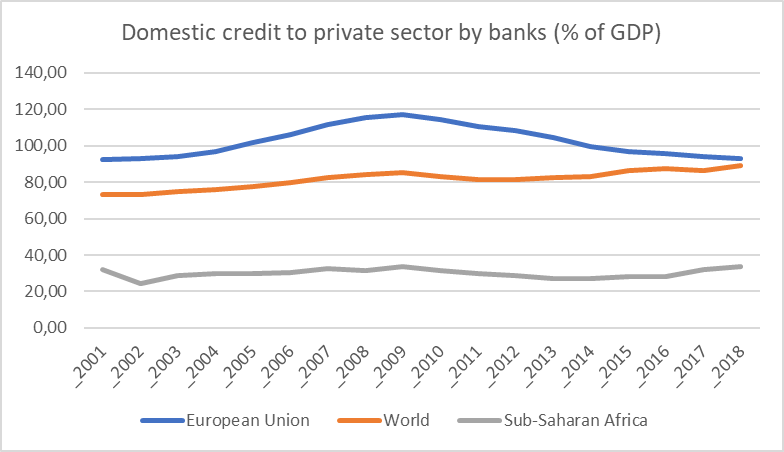

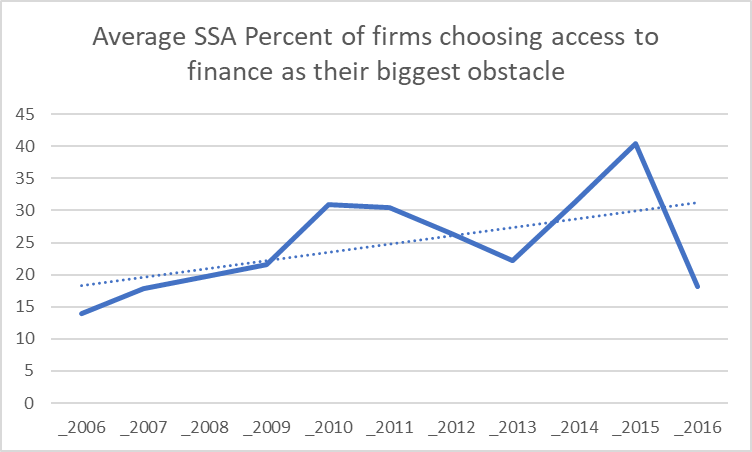

All of these are rooted in grains of truth, but yet some entrepreneurs make it out of the start-up stage thanks to an innovative idea, an indispensable product or a lucky gamble, and find themselves incapable of reaching the next stage of growth due to insufficient or inappropriate financial products. This developing world issue is just as prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa – the average African country’s rank on the “getting credit” indicator is 113 out of 1903.

The upscaling and downscaling conundrums

The oft-cited “missing middle” of SME finance is the underlying rationale for FS Impact Finance’s crowdinvesting platform concept that will roll out in 2020 in Ghana – SMEs do not have sufficient or appropriate access to finance. The gap is described as in the “middle” as it is in a niche between the microentrepreneur lending covered by microfinance institutions, and corporate and public lending covered by commercial banks.

Many development finance professionals have looked towards these financial institutions to either upscale (MFIs) or downscale (banks) to address the gap, yet few have done successfully – MFIs may have the expertise to look at cash flow modeling to determine creditworthiness and the network to conduct the monitoring, but many MFIs prefer to stick to their target clientele (microentrepreneurs and rural households), do not have the liquidity to meet the higher financial needs of SMEs, or the product range (letters of credit, overdrafts, mid-term working capital loans, etc.).

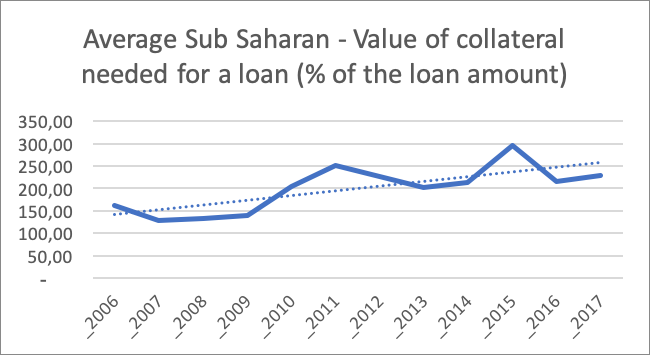

Many banks have attempted to use their financial capacity to fill the niche, but they have a conundrum: they have trouble identifying what they consider creditworthy enterprises (those that have a lot of collateral) and have quite profitable and low-risk opportunities in government treasury bills.

The time for mesofinance?

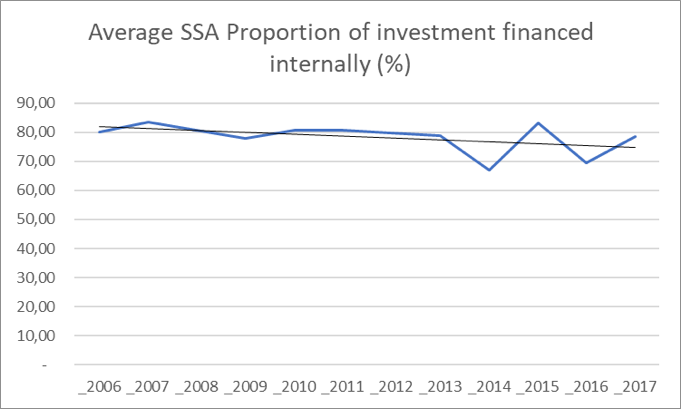

Put simply: MFIs have some of the knowledge base and banks have the money, but SMEs have mostly been forced to navigate with own equity, insufficient funding from MFIs and frustrating relationships with banks. In this landscape, a new type of financial institution is emerging in West Africa, which is not venture capital, not banking, instead a modern form of microfinance. The wailed for “mesofinance” niche is starting to be filled by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) that focus their business model on established small businesses – using classical microfinance cash-flow based lending methodologies, overdraft facilities, and partnerships with banks or telecommunication companies for international transfers.

Thus far, many of the SMEs financed originate from the trading sector, but during our interviews with some of these “quasi-banks” there has been interest in acquiring agri-finance expertise to propose larger-scale solutions to small exploitations, and innovative ways of applying the value chain methodology to manufacturing enterprises: similarly to agricultural value-chains, manufacturing requires raw materials, transformation, wholesalers and retailers, and each of these actors need finance.

These mesofinance operators have also benefited from lower entry costs thanks to use of innovation in financial technology: network connectivity in the field that allows for smaller branch sizes, quasi-automation of loan analysis, use of electronic money when appropriate and large amounts of data for better analysis of ways and means. While banks are still relying on the expensive brick and mortar model, and MFIs have struggled with the finding the investment capacity to go full scale digital, here again these fit a niche.

There is still a long way to go for the NBFIs to achieve the scale to properly address the full need of small entrepreneurs in West Africa, and thereby support sustainable growth and increasingly attractive job opportunities in the formal sector. Further, in the financial sector any successful new developments should be observed with care – as there is often a lag between making profits in the short term and achieving sustainability in the long term – in that lag bubbles can boom and bust. Yet, let us not preemptively throw the baby with the bath water, and instead nurture this development, hoping that other economic actors will take notice and also further contribute to the emergence of the African “Mittelstand”. FS Impact Finance will continue to use its resources and business model to support this development.

Footnotes:

1 World Trade Report 2016: Levelling the Playing Field for SMEs, World Trade Organization

2 World Employment and Social Outlook 2017: Sustainable enterprises and jobs – Formal enterprises and decent work, International Labor Organization

3 Doing Business 2020: Region Profile Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank